The Reality of Australia's Investment Landscape and What Needs to Change

“If you are unwilling to assume risk, and only want to make safe investments in farmland and real assets, you are not the supporter regenerative farmers need.

You are unlikely to have a significant impact on regenerative agriculture as a whole."

— John Kempf , RFSI 2021

The State of Play

Let's do a quick scan of the investment landscape in relation to food and farming.

A brief summation — it’s not looking so good.

Dominant patterns of the current investment landscape serve to reinforce and exacerbate, rather than shift or ameliorate, the harmful and inequitable patterns of our dominant industrial systems.

4°C portfolios

In 2019, the Food and Land Use Coalition found that the food and agriculture portfolios of most financial institutions are “4-degrees Celsius” portfolios - i.e. they are aligned with a 4-degrees Celsius global warming scenario.

Net negative impact

Current private investments that are adversely affecting the biosphere outstrip those that are enhancing natural assets, and these trends are strongly shaped by financialisation — ‘the increasingly powerful role of financial actors, motives and trends in shaping global economic activity, which has become a prominent force in the corporate consolidation across food and farming’ (IPES 2021).

Risk and Exposure

Many of the assets in the sector held by financial systems, are linked to the major public health challenges and are key drivers of the climate crisis. The deep exposure of these assets and associated finance, particularly in the agricultural sector, to physical climate risk, ‘poses a threat to global financial stability, as identified by the financial regulators gathered under the Network for Greening the Financial System' (FOLU).

Destabilising

Recent studies have shown that this financialisation, and in particular investors providing capital to the large corporations trading in certain commodities, is playing a key role in destabilising ‘Sleeping Giants’ in the climate system — those parts of the earth system such as the Amazonian and Boreal forests which, when altered to a certain point, drive tipping point feedbacks with large impacts on the climate system as a whole (Stockholm Resilience Centre).

Inequity

The fallout of degrading planetary health and associated economic shocks tend to have more severe impacts on low-income countries and/or individuals, resulting in amplified inequalities in society.

(Information adapted from FOLU 2019:54, Dasgupta 2021: 474; IPES 2021:18; Stockholm Resilience Centre 2022: 13,14)

The Good News?

Shifts are happening in terms of awareness and activity around sustainability and climate issues, with ESG and climate investments seeing rapid growth over the past decade. (TIIP 2022: 2).

Since 2010, new accounting and reporting frameworks for ESG and climate risks and impacts have been developed or slated for development, including the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), established in 2015.

While these shifts are heartening, the reality is:

- ‘Many existing sustainable investing approaches do not address the systemic nature of many of today’s most pressing social and environmental challenges’ (ibid).

- The low accuracy of ESG reporting requirements ‘provide a false sense of progress and an unverifiable promise of sustainable investments' (Crona et al. 2021; see also Crona 2021.).

- There are nowhere near the funds being allocated to match the scale the IPCC has found is needed — with capital flows to fossil fuels still greater than what is being spent on climate mitigation and adaptation (Pollination 2022: 7).

The rise of ‘sustainable investing’ has seen an increasing interest in financing in regenerative food and fibre systems. In the last 5 years in particular, there has been a plethora of research reports, forums, podcasts and organisations exploring investment opportunities, mapping what needs investment, with a particular focus on the agricultural component of the system, and profiling existing activity (CREO 2021, Croatan Institute 2019, EU 2022).

But the concern rippling across the regenerative sector is that the investment and financial community are entering the conversation with the same status quo operation modes that have so negatively shaped the industrial food and fibre regime.

Patterns of corporatisation, power imbalances across the value chain and extractive forms of finance that prioritise economic return over ecological and social returns are not fit for purpose to work with regenerative systems, and in fact, run counter to the impacts these evolving systems are working to create.

All of this points to the pressing need to shift current conversations beyond their focus on what and where needs investment, to take a deeper dive into how investment is being conceived and structured.

A growing field of practice and theory across regenerative finance is underpinned by the foundational understanding that in order to transform our systems we have to transform the how and why of capital flows. A key voice in evolving this conversation is John Fullerton of the Capital Institute who has developed a framework for regenerative economies, beginning with the foundational understanding that 'the so-called “financial economy” is an abstraction that must be reined in, reconnected, and subordinated to the needs of the real economy' (Fullerton:10). Planet Earth.

How much of this new form of finance is at play in food and fibre?

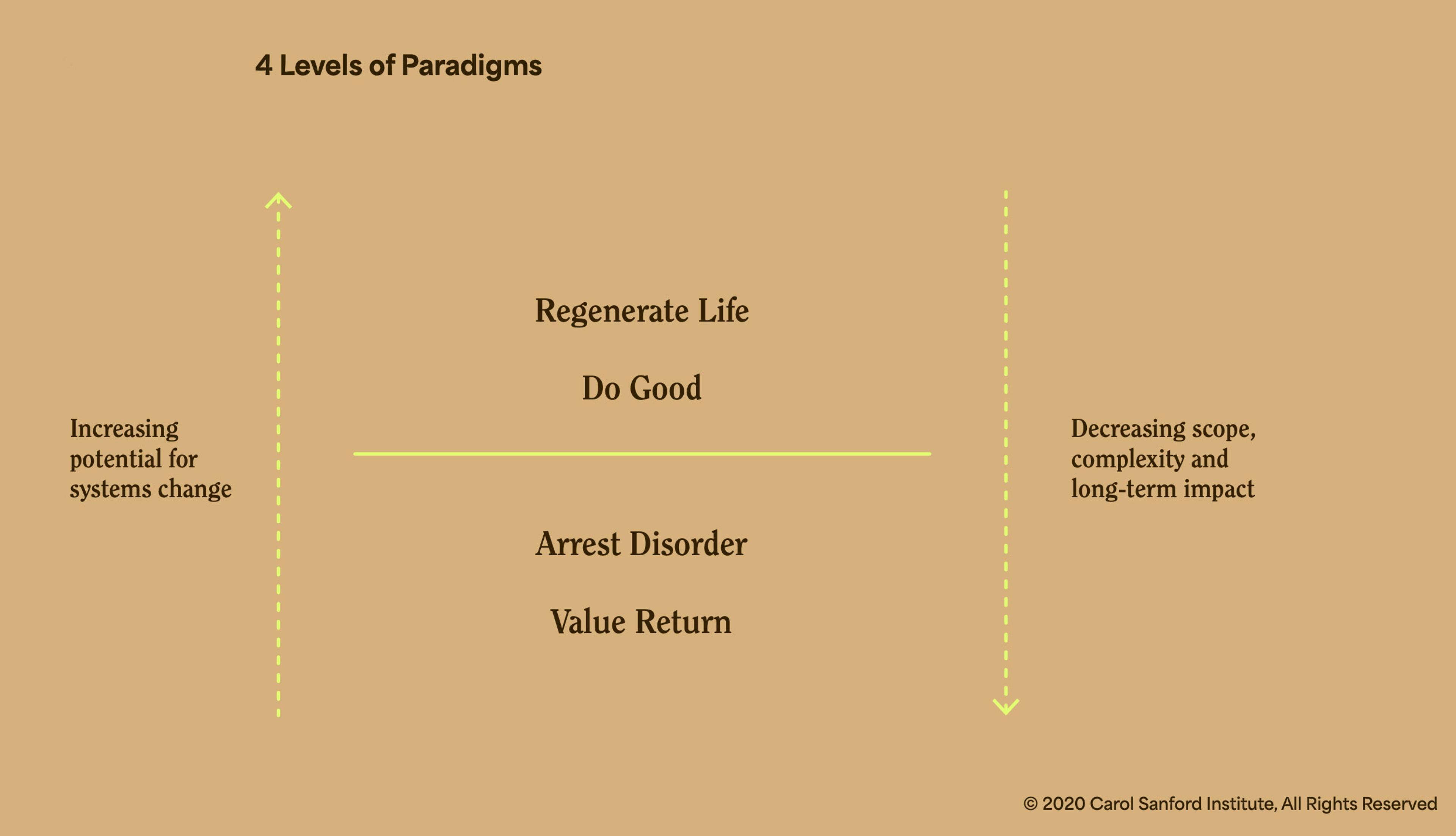

We've drawn on a few tools to help us map and visualise the current state of play, including the 4 Levels of Paradigms, developed by the Regenerative Economy Collaborative and Carol Sanford Institute, to delineate the underpinning of the thinking and actions of stakeholders in a system.

4 Levels of Paradigms: Investing in Regenerative Food & Fibre Systems

The figure is based and adapted from the work of Ethan Soloviev expanding the 4 paradigm framework to help delineate the investment paradigms at play in food system investment (2021).

Value Return Paradigm

- Investment motivation: A focus on short-term financial outcomes. Get in. Make a buck. Get out.

- Investors hold power and control and relationships between stakeholders are limited to financial transactions.

- Outcomes: Short-term economic gain for a few, at social and ecological cost

- Example: Farmland and Agribusiness investments that derive value return from productivity at all costs - i.e. land clearing and 'improvement'.

Arrest Disorder

- Investment motivation: Making a profit from efficiency, optimisation and centralisation.

- Relationships are top-down and narrowed in on a single component of the value chain.

- Outcomes: Increased efficiency and centralisation of supply chains, value return and control.

- Example: Investing in tech that reduces fertiliser, pesticide and water use or robotics and machines that replace human labour.

Do Good

- Investment motivation: A sincere desire to create positive change.

- Investors and philanthropists define ‘doing good’ and impose desired outcomes on the projects they fund.

- Outcomes: Short-term change that is limited in scope.

- Examples: Investing to 'do good' (improve soil health) as opposed to 'do less harm' (arrest disorder - reducing fertiliser use) - by investing in a large corporate biological inputs company that still centralises profits and control away from rural and regional communities.

Regenerate Life

- Investment motivation: Co-create open-ended transformation

- The humility paradigm, enabling co-creation across multiple stakeholders who are investing financial and non-financial capital.

- Outcomes: Place-based, long-term transformation that is grounded in the knowledge of people in that place.

- Examples: W+ Standard Kasigau Corridor Community Ranches project in Kenya (Case Study - P. 102)

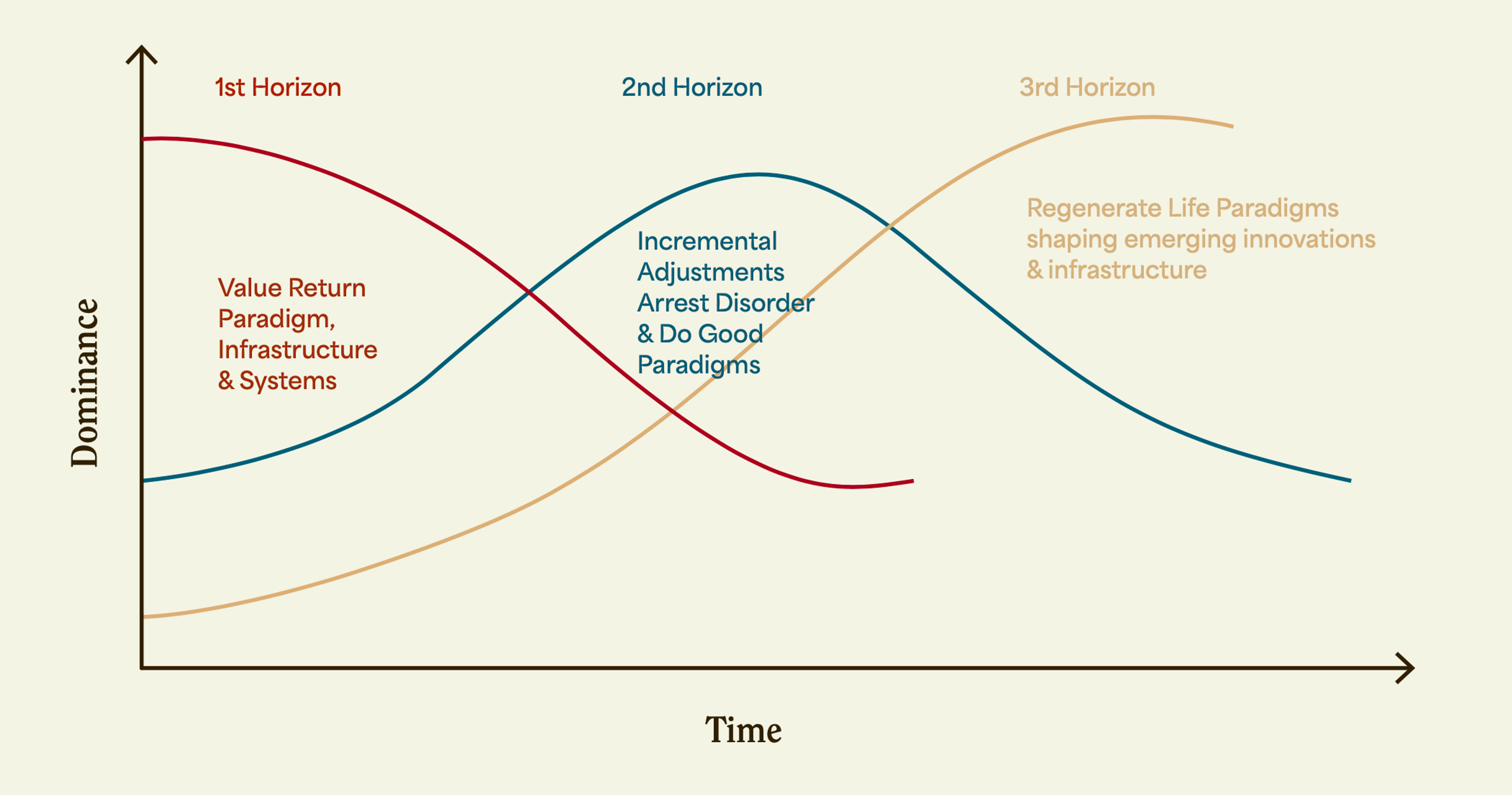

3 Horizons Framework

To understand where we sit currently in investment flows and transformative shifts, we have merged the 4 Levels of Paradigm with the 3 Horizons Framework — developed by the International Futures Forum as a tool 'for making sense of and facilitating cultural transformation and exploring innovation and wise action in the face of uncertainty and not-knowing’ (Wahl 2016).

For a brief overview of the 3 Horizons Framework we recommend viewing this video by Kate Haworth.

If you look at the framework you will see that:

- Horizon 1 investment activity is dominant - otherwise termed business as usual or 'world in crisis' (ibid).

- Horizon 2 is increasing in dominance - this is where incremental and transitional shifts away from business as usual are taking shape.

- Transformational Horizon 3 activities are occurring in rare pockets of the present.

The framework 'draws attention to the three horizons always existing in the present moment, and that we have evidence about the future in how people (including ourselves) are behaving now’ (Sharpe, 2013: 2).

What mapping the current state of play this way makes visible:

Horizon 1 (H1) - Business as usual is dominant.

- H1 is the current dominant way of doing things. This is business as usual. Value Return is the core operating paradigm which means the key motivation and focus is on maximising financial return.

- There is innovation occurring here at the H1 level, but mostly to maintain and extend the status quo in terms of power, wealth and control.

Horizon 2 (H2) - Transitional investment activity is growing.

- H2 is the ‘transition and transformation zone’ (Centre for Impact Innovation 2021) where new approaches to investment are evolving and being tested. Here, investment sits across the Arrest Disorder and Do Good paradigm levels — innovating to ‘do less harm’ and fix problems but usually focusing on single nodes and components of what are deeply complex systems.

- There is a lot to be learnt from existing attempts to transition in the growth of H2 in terms of ESG and impact-driven investment and philanthropic activity — including the urgent need to start delineating between what is shifting us towards transformation and what is holding us in place.

Horizon 3 (H3) - Rare pockets of transformation are at play.

- H3 is the Regenerate Life investment paradigm level — holistic,

- place-based investments focused on generating and enabling new potential and systems and working not with recipes and prescriptions, but with emergence and values.

- Rare pockets of H3 transformation occur in the present — showing us that these deep shifts are possible but are extremely rare. (These H3 'pockets' are the focus of many of our case studies in the chapters ahead).

- Given these are the interventions that can actually shift the system, we need to focus a much greater proportion of investment and capital flows into this space of transformation, within the paradigm of regenerating life.

The latest IPCC report emphasises (again) that we are running out of time and the dominance of business as usual cannot continue.

To shift us onto a transformative trajectory for our food and fibre systems, we need a whole ecosystem of enabling, regenerative capital to work alongside us as ‘co-creators’ (Haggerty 2022) in experimenting and learning our way towards Horizon 3 and a regenerative future.

At Sustainable Table we have drawn a map of the pathways - existing, forgotten, yet to be made — that can leverage us towards transformation, from H1 into H3 and the unfolding work of regeneration.

This article is an extract from Regenerating Investment in Food and Farming: A Roadmap.