Aboriginal Economics

Gaala is a Gungalu and Birri-Gubba Woman born and raised in Brisbane. Currently a PhD candidate at the University of Queensland Business school, where her research is investigating Aboriginal Governance in the SE QLD region, Gaala has an MBA from Griffith Business School and is a former Fellow of the Griffith University Yunus Centre. A former Chair of the Food Connect Foundation, Gaala was a steering member for the Social Enterprise World Forum, held in Brisbane in September 2022, and runs/founded Humanize Media.

I write from my own Gungalu and Birri-Gubba perspective, and by no means seek to encompass the various views of First Nations people across the continent. In this, I acknowledge that a great attribution of Aboriginal peoples is the cultural diversity that we have maintained, despite colonisation. I also acknowledge our Elders and ancestors that have provided us with a wealth of knowledge, courage and grace — tools to continue the legacy of work in maintaining our culture and building a healthy future for our future generations.

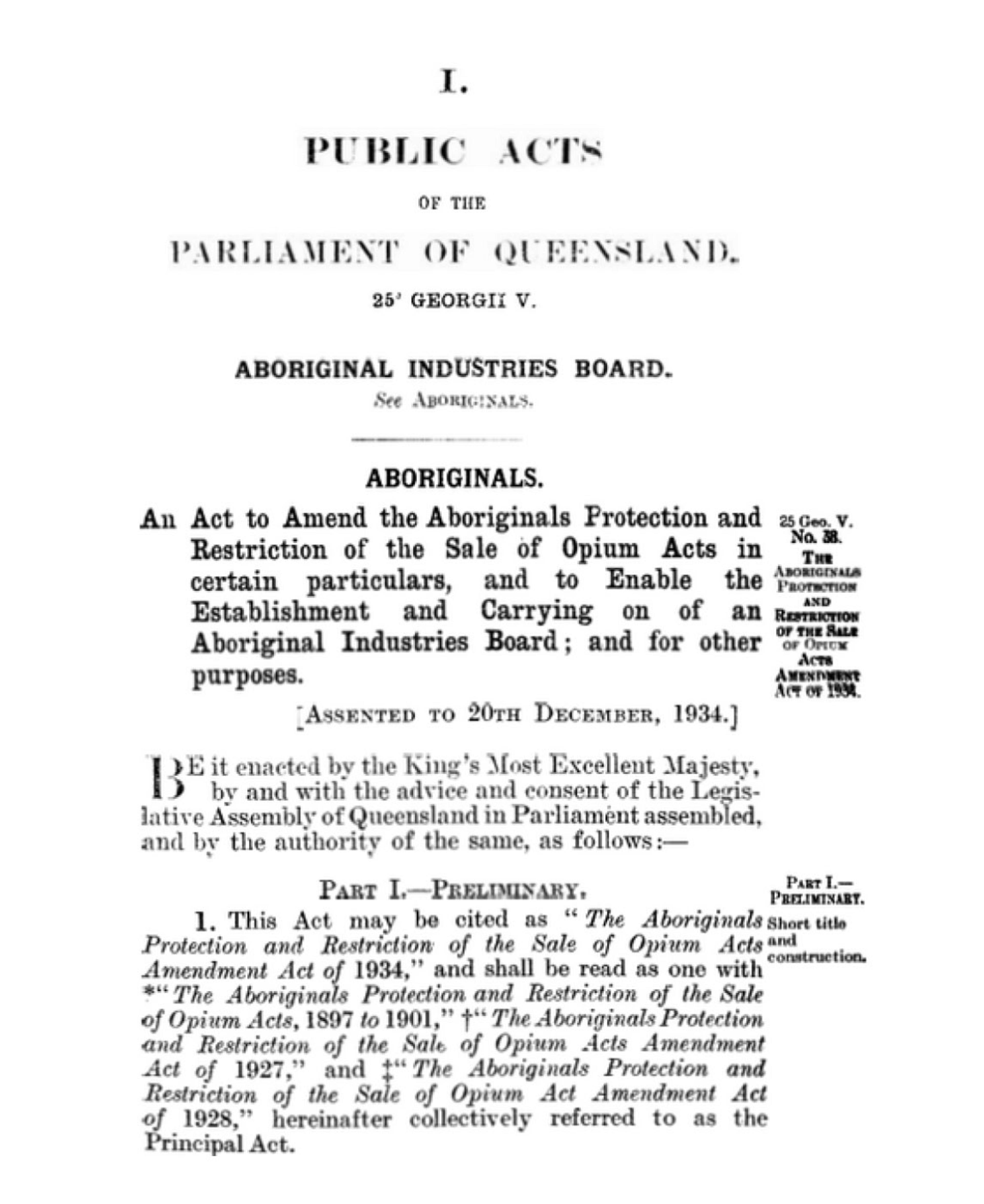

The economic relationship between the government and Indigenous peoples has been one of legislated dispossession. As late as the 1970s, Indigenous peoples in Queensland were still governed under the Protection of Aboriginals and the Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act. The infamous Act controlled numerous aspects of the lives of Indigenous peoples, including all financial matters. And while this may seem like long ago to some — this was my Father's generation.

14891: 17. No person shall have any right or remedy to or Debts against any property or money held by a Protector or superintendent for or on behalf of any aboriginal or half-caste on account of any debt due and owing to such person by such aboriginal or half caste for or on account of any money lent or goods supplied to him on credit unless such money or goods have been so lent or supplied with the prior consent of a Protector or superintendent.

14894: 24. If any half-caste is exempted from the provisions of this Act and the Principal Act, the Minister may make such exemption subject to such conditions as he shall think fit, including a condition that all money or property belonging to such half-caste and held in trust for such half-caste by a Protector shall remain subject to the control of a Protector.

14895: 2: ...the labor of aboriginals, half-castes, and all other persons living upon a reserve, and of all stock and other property thereon; and the control and supervision of all trading transactions of aboriginals and half-castes, whether upon a reserve or not.

Considering the mechanisms of wealth creation, including attaining wages via labour, accessing finance, and the flow of generational wealth via inheritance throughout the previous 2 centuries — Indigenous peoples were lawfully excluded from these basic economic rights.

One of the most prominent legacies of these laws is the persistent attitude that Indigenous peoples are financially irresponsible and incapable of making appropriate financial decisions. This stereotypical view has seen billions of dollars directed to Aboriginal affairs via flawed policy — rarely determined by Indigenous peoples from the communities these programs were designed to benefit.

Aboriginal peoples have never been given true self-determination over their economic affairs, and the lack of economic progress in our communities illustrates the importance of this participation.

Memmott & Richards (2021) wrote:

Although many Queenslanders are possibly ignorant of the Act’s effect and long-term implications, the application of this racially-based set of laws affected — and continues to have an impact on — every Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family and individual in this State... The complexities and perceptions of law, race, colour and social status informed the creation of this legislation which effectively dictated the futures of Indigenous Queenslanders for decades and generations to come.

I encourage people to reflect on the extreme wealth that has been created on the back of Aboriginal dispossession via land, resources and labour.

While Australia has been the lucky country for countless white Australians and other migrant communities — those same economic opportunities were never afforded to Indigenous peoples based on the racial discrimination that has permeated almost every level of the economic system. It is these racist ideologies that have continued to keep many Indigenous peoples living in poverty.

If we look at the justice system, healthcare system, financial institutions, employment — any major systemic structure that impacts the economic condition of individuals — there is guaranteed to be current and historic evidence of racial discrimination towards Indigenous peoples. It is the culmination of these factors that have contributed to the ongoing economic state of Indigenous peoples in this country.

Goenpul scholar, Distinguished Professor Aileen Moreton—Robinson states: ‘Our socio-economic position is the result of government policies and the theft of our lands and resources. It is therefore government responsibility to change their addictive behaviour to Indigenous welfare and make the right choices for the necessary legislative and economic reforms to improve the Indigenous poverty it has created since 1788’.

While the legacy of colonialism continues to impact our economic position, there is also the consideration of what money means to Indigenous peoples and how our views of wealth and success differ greatly from mainstream society.

We as Indigenous peoples in this country have a different relationship to money — money is viewed as a resource and all resources are fundamentally considered communal in varying degrees. Money is not meant to be hoarded; money is a tool. It is important to consider that money is not viewed or considered in the same regard as natural resources — natural resources are alive, they have spirit. Money is dead, lifeless, spiritless. Money is a commodity that has less life or spirit than a leaf or piece of soil.

A study that looked at Aboriginal perspectives on white culture and the costs of neoliberalism saw a group of Aboriginal people interviewed about their thoughts on white Australian values and behaviours: most respondents believe most Australians live in ways that go ‘against nature’, at high cost to the social fabric and environment.

Among the responses were the following:

Di: We say white fellas have dollar dreaming ... to White fellas the dollar is sacred ... That's their way of life, their dreaming, their culture.

Fred: It's a good thing, because they work for their money. But I find them to be sad and alone and not to have any friends, because whatever they work for, it's their things. Whereas for us, whatever we work for, we like to share and make everyone around us happy.

Money is not central to wealth in Indigenous cultures — wealth is better measured via the richness of our relationships to people, land and spirit.

We, as Indigenous peoples, cannot achieve economic sovereignty via government and other institutions, who refuse to give us meaningful decision-making power and determination of economic resources allocated for the betterment of our communities. This is apparent with the often excessively conditional funding distributed by government institutions and funding bodies that administer resources to Indigenous peoples.

Funds provided by the government to boost the Indigenous economy are distributed via the terms and conditions determined by policymakers — which are often hyper-conditional, constricted and exclude many valuable members of our communities. This sees Indigenous businesses often offered services, training, and opportunity rather than capital. These constrictions highlight the lack of trust in Indigenous peoples to handle finances, but in reality, further inhibits the capacity of Indigenous people pursuing economic development.

Over the past decade, we have all heard about the ‘Indigenous Business Boom!’, billions of dollars injected into Indigenous business but we have seen very little impact in communities. Among some of the possible explanations for this include black cladding, individuals with a pro-capitalist agenda and businesses not reinvesting in community — essentially operating with an individualistic mindset.

There has been a shift from our inherent traditional values regarding money, which is undoubtedly an outcome of assimilation. Assimilation is a contentious issue, but we as Indigenous peoples must question ourselves regarding our decision-making processes to ensure that we are striving to support Indigenous-led solutions that benefit our people, our country and our future generations. We, as Indigenous peoples must remember that our Indigenous terms of success and wealth differ greatly from those of dominant society. For us as Indigenous peoples, we must be reflexive in our approaches to decision-making that affect our communities and our country, reflecting frequently on our own motives and an awareness of those non-Indigenous influences. Governments, funding bodies or organisations also have an obligation to ensure that any economic investment into communities is made via protocols that empower and benefit all and not just a select few.

The above discussion reinforces the need for Aboriginal-led economic solutions based on Aboriginal terms of reference. The basis of economic sovereignty must encompass our unique assertion of sovereignty which is inseparable from land, community and spirit.

As Kaava Watson explains: ‘People talk about sovereignty as though it exists in structures or in foreign powers. Sovereignty exists within our communities, within our people — it's the processes in which we all participate — it's the processes in which we come together and decide how we want to do things our way’.

When we as Aboriginal people talk about economic sovereignty, it is something that inherently encompasses clean air, clean water, healthy country, community and an idea of wealth that is fundamentally informed by our cultural values.

We as Aboriginal peoples have never been given an adequate opportunity to rethink and rebuild modern economic systems based on our governance and values.

Building an economic system that encompasses land/Country, people and balance is what is needed in today's society as we face the climate crisis, extreme wealth gaps, social inequality and unsustainable resource use.

We are striving for a better future for all future generations. Aboriginal knowledge and governance will benefit everyone — not just us.

While we are economically unequipped to create large-scale impact — we will use what little we have to continue the fight of our old people, to create a life of song — for people and Country.

As my father once wrote:

“People will know the work is helping when we are able to become more self-sufficient within family households and form neighbourhood networks based on goodwill and respect.

Trees might start growing back and help the little things to revive. When we create an economy based on respect for nature and people, all those things can happen.

If that situation comes about, the big money mob might find they are irrelevant and obsolete, because a goodwill economy might take over theirs."

Song of A Rainbow Warrior

— 1985 (Adapted 2012).

We are just like other people

Who wish life to be a song.

Instead, the good things of existence

Are suppressed by so much wrong.

But we will not fight these evils.

To compete means win or lose.

Before a life of conflict,

It's a life of song we choose.

No, we'll not enter competition

With money, robot and the gun.

We will create a world that's proper,

Along with other children of the Sun.

Written by R. Watson, Gaala's father

This article is an extract from Regenerating Investment in Food and Farming: A Roadmap.